The Intersection of Herzl and Jabotinsky

"Herzl Street" is a major thoroughfare in 52 Israeli cities.

It’s not just in major cities like Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, or Haifa—52 different cities feature a street named after Theodor (Binyamin Ze’ev) Herzl. Their common denominator: they are overwhelmingly Jewish and were established in the 20th century, either before or after Israel's declaration of independence.

In fact, most of Israel’s established and largest cities chose to name a central street after Herzl, honoring and immortalizing the man regarded in Israeli heritage as the "Visionary of the Jewish State"—an iconic figure etched into the Zionist narrative upon which Israel’s independence is built.

Where won't you find a Herzl Street?

In cities with an Arab majority, such as Tayibe or Umm al-Fahm, and in Jewish Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) cities like Elad or Beitar Illit.

This is the essence of the story told here, in three chapters: a look at the most extensive commemoration project visible throughout the State of Israel.

This "project" accompanies citizens as they leave their homes, go shopping, or travel by car or bus. They see the famous name echoing on street signs, appearing on Waze maps, and taking its place within the bureaucratic maze of forms requiring an address. Every street name commemorates a figure that seeps into the collective consciousness, weaving itself into the national narrative that dictates the character of education, economy, culture, and the lifestyle of both the majority and the minority.

The facts on the ground prove that the Zionist narrative still reigns supreme.

Herzl is the most prominent proof of all.

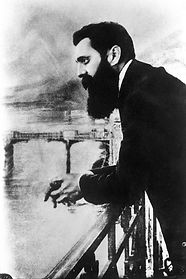

Theodor Herzl in the iconic photo on the hotel balcony in Basel, Switzerland, 1901.

Theodor Herzl is the longest-standing commemorated figure in the modern "national pantheon" of the Jewish people.

The writer and jurist who led the Zionist revolution was a symbol and a model of leadership even during his lifetime, earning respect and admiration even from those who disagreed with his views.

He likely understood his own status, devoting himself to photographers and painters who co-staged images with him—images designed to be distributed to every media outlet and information provider of the time. These portraits achieved wide circulation during his life, and even more so after his death, when he became synonymous with the return of the Jews to their land and the modern history of Israel.

His sudden death in 1904 at the age of 44—at the height of his influence, when the Zionist movement was already convening the congresses he initiated and establishing settlements in the Land of Israel—sent shockwaves through the entire Jewish world, and most profoundly through the Yishuv (the Jewish community in the Land of Israel).

His commemoration was only a matter of time.

Less than a year after his passing, the Village of Rishon LeZion (which later expanded into a city) decided to name a street after him. Later, in 1907, a residential neighborhood in Haifa was named in his honor ("Herzliya"). In 1910, the "Tel Aviv" neighborhood was established, named after the Hebrew title of his book (Altneuland) detailing the vision for a Jewish state. That neighborhood grew into the city of Tel Aviv, with Herzl Street at its heart and the first Hebrew high school, "Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium," named after him.

Since then, his name and legacy have ascended to the top spot among the legendary figures of Jewish history—surpassing even the great philanthropists Rothschild and Montefiore, and ahead of Maimonides (Rambam), Yehuda Halevi, or Zionist leaders like Wolfson, Pinsker, Ahad Ha'am, and Arlosoroff.

Herzl is the only individual explicitly mentioned by name in Israel's Declaration of Independence. This ensures his status as a lasting historical symbol even today, after 120 years of Zionism—a national icon that accompanies Israelis everywhere, much like the national anthem "Hatikvah," the Star of David, and the blue and white of the national flag.

Judging by the bustling traffic on the streets bearing his name—and adding Mount Herzl (which has achieved a nearly sacred status), the city of Herzliya, museums, forests, ships, hotels, banknotes, Hebrew songs, and even the first and last names of citizens who proudly bear his name—this is a phenomenal act of commemoration. It is one of the pillars upon which the narrative of the Jewish people in Israel and throughout the world is based.

The headstone on Herzl's grave at the summit of the mountain named after him.

In Israel's 'National Memory Department,' Herzl has a few serious competitors, such as David Ben-Gurion—with streets, neighborhoods, a respected university, and an international airport to his name—and Yitzhak Rabin, who in a short time has accumulated numerous streets, neighborhoods, schools, and a heritage center.

But the most prominent competitor is Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

Unlike Herzl, Jabotinsky entered the "National Memory Department" as a revered but controversial political figure, one who was not accepted by the Zionist establishment that drove the founding of the State of Israel.

His image did not hang in public institutions, and even today, it remains relatively unfamiliar to many Israelis. During his lifetime, his legacy was recognized only by a small segment of the Jewish public—those who adhered to the Revisionist worldview, which was then on the right wing of the political map. The Revisionist ideology was considered too right-wing and was marginalized by the Zionist establishment. To the leadership of the pre-state Jewish community, Jabotinsky was seen as too nationalist, or even "fascist."

And yet,

Jabotinsky managed to pave a way to the top of Israel’s commemoration table with some exclusive achievements: 55 streets are named after him in various cities across the country—even more than streets named after Herzl or Ben-Gurion. One "Jabotinsky Street" crosses three cities in a single stretch—Ramat Gan, Bnei Brak, and Petah Tikva—and is perhaps the longest street in the country.

Named after the leader of the Revisionist movement are also residential neighborhoods, a public park, and an institute for the preservation of his political teachings—an especially impressive feat for someone who was only accepted into the national consensus after his death in 1940, and many years after the state's establishment.

Ze'ev Jabotinsky – a revered leader whose image did not grace the streets

Like Herzl, Jabotinsky also died relatively young, at the age of 59.

His sudden death sparked mourning that crossed party lines and political ideologies. For example, in Haifa—a socialist city where most residents belonged to left-wing parties—the municipality decided to commemorate him by naming a street after him just months after his death. In Tel Aviv and Ramat Gan, led by mayors from right-wing parties, officials hurried to honor his memory by naming major streets after him.

To whom is this commemoration so important?

And why is it significant that one is in the consensus while the other is not?

Find out in the next chapter:

The Intersection of Herzl and Jabotinsky: Commemoration and Heritage on Israel's Streets—A Three-Part Series: